Our History

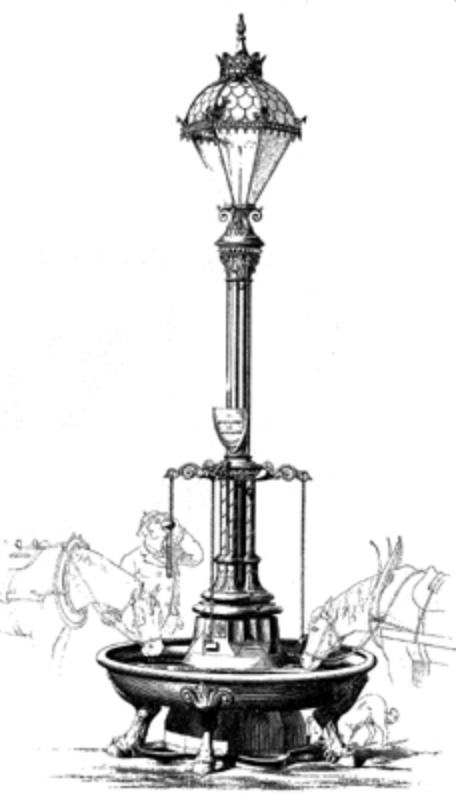

Adye Douglas Water Trough

In 2008 Glasgow Engineering were requested, by the Launceston City Council, to inspect cracks that had formed in the central base area of the Adye Douglas Water Fountain. As the base material is cast iron it was decided that the only approach to repair was to remove the fountain back to the Glasgow works for welding to be undertaken under controlled conditions. The fountain was removed from its existing site on the Elphin Road, High Street intersection, upon which, it was discovered that the base had fallen into further disrepair than first thought. It is believed that some 60 years ago the water trough, in its original position in the middle of Elphin Road, was damaged in an incident involving a truck. The impact from that collision resulted in some of the damage that we see today on the water trough. The base plate had fractured or delaminated in the same manner as shale or slate and fell to pieces when lifting the trough with the crane. Other previous poor quality repairs were discovered as well. One of the horse’s legs had many cracks and missing sections. This was strapped and bolted together with mild steel flat bar and then the leg was filled with lead. The dog dishes had nearly corroded through and were badly cracked and pitted. Glasgow Engineering undertook extensive research on the fountain and its manufacturer Walter MacFarlane. It was then discovered that the fountain was actually a water trough and was designed for supplying water for drivers, horses and dogs. The original trough had a central lamp post and was pattern number 27 in the Walter MacFarlane catalogue.

The trough was a gift to the City of Launceston by Adye Douglas, an alderman of the town since its incorporation in 1883. At some stage through the trough’s life, possibly not long after the collision, the trough was relocated and converted into a fountain. When this was undertaken the centre column was shortened so the top water dish wasn’t as high. Further investigations discovered that there were only a handful of pattern number 27 left in the world, one other being in Mowbray, a suburb of Cape Town, South Africa. It was at this stage Glasgow Engineering contacted the Launceston City Council to relay the significance of the water trough and its restoration. It was felt that it should be returned to its former configuration with the central lamp post. Negotiations were undertaken between Lionel Morrell of the National Trust, Chris Bonner of the Heritage Council and Andrew Smith of the Launceston City Council, with all parties in agreement for the restoration to be undertaken. Glasgow Engineering inspected the castings and while there was evidence of extensive pitting in the main bowl, it was free of plumbago. Plumbago is the degeneration of cast iron caused by being immersed in water for long periods of time. The base plate was beyond repair and could not be salvaged. The damaged leg could be repaired and missing sections replaced. Overall, the condition of the water trough was poor but retrievable.

The whole water trough, including the acquired lamp posts, was sand blasted clean from all paint and corrosion for restoration to take place. A new base plate was manufactured from mild steel plate and hot dipped galvanized. The main bowl was set up and leveled to the base.

The dog dishes were

welded up and all cracks repaired.

The horse’s leg had the lead

melted out from inside and the broken separate pieces were welded together. A new section of cast iron was cut to shape

and welded into the position of the missing pieces. The cast shape was then

replaced, by hand, using a die grinder.

The post was cut to size and re-welded and a flange was fitted to the base so that it could be bolted to the water trough. The height of the post was calculated using the original drawing and the existing water trough bowl. The second post had the column Corinthian capital removed and inverted and welded to the Corinthian capital on the main post, as to match the original design as close as possible.

Sir Adye Douglas (1815-1906), lawyer and politician, was born on 31 May 1815 at Thorpe-next-Norwich, England, son of Captain Henry Osborne Douglas and his wife Eleanor, née Crabtree; his grandfather was Admiral Billy Douglas. Educated at schools in Hampshire and Normandy, he served articles with a legal firm in Southampton. He decided to migrate to Van Diemen's Land, sailed from London in the Louisa Campbell and arrived at Launceston in January 1839. He was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court in February but soon went to Port Phillip, where he ran sheep with his brother Henry near Mount Macedon. Late in 1842 he returned to Launceston where he founded a legal firm which still operates. Over the years he had several partners; the last, George Thomas Collins (1839-1926), had been articled by him. Douglas built up a flourishing local practice and acted for many important clients in Victoria. Deeply interested in the colony's welfare, he realized that no progress was possible while convicts were sent to Tasmania. He became one of the founders of the Anti-Transportation League. He was elected one of the first aldermen in the Launceston Municipal Council, established in 1852 and held office until 1884, serving as mayor in 1865-66 and 1880-82.

Douglas was defeated at the elections for the first part-elective Legislative Council in 1851 but won a Launceston seat in 1855. He was prominent in the council's action against John Hampton, moving his arrest and the appeal to the Privy Council in defence of the Speaker, Michael Fenton. Under the new Constitution in 1856 he represented Launceston in the first House of Assembly where he succeeded in introducing a bill to provide a water supply for Launceston but failed to win support for a preliminary survey of the Hobart-Launceston railway. In 1857 he resigned and travelled in America, France and England. He became even more impressed by the need for railways. On his return he began to advocate the Launceston-Deloraine railway and in 1865 carried the bill for it against strong opposition; the first sod was turned by the Duke of Edinburgh in 1868.

In the House of Assembly Douglas represented Westbury in 1862-71, Norfolk Plains in 1871-72 and Fingal in 1872-84. He then became premier and chief secretary and was elected for South Esk to the Legislative Council, where in 1885 he carried a bill for the appointment of an agent-general in London. He had represented Tasmania at the Sydney convention from which the Federal Council of Australasia was evolved. In 1886 at its first session in Hobart, Douglas predicted a 'United States of Australasia … independent of the little island in the Northern Hemisphere'. Called to order, he reminded members of the toasts of forty years ago to the 'Australian Republic'. In March he resigned as premier after appointing himself the first Tasmanian agent-general in London. He attended the Colonial Conference in 1887 but was recalled because his negotiations with the Tasmanian Main Line Railway Co. had failed. He represented Launceston in the Legislative Council in 1890-1904 and was its president in 1894-1904. As an active delegate to the federal conventions in 1891 and 1897-98 he won praise for his physical endurance; to (Sir) Isaac Isaacs, 'he looked like a Hebrew prophet with his long locks and long beard, speaking with kindly wisdom to his people'. Douglas was knighted in 1902, ranked by the governor as 'the first among living Tasmanians'. He died at his home, Ryehope, Hobart, on 10 April 1906 and was buried at Cornelian Bay cemetery.

Douglas had three sons and a daughter in the 1840s. On 10 July 1858 in London as a widower he married a widow Martha Matilda Collins, née Rolls. At Launceston on 18 January 1873 he married Charlotte Richards, by whom he had a daughter Eleanor before she died aged 22 on 23 July 1876. On 6 October 1877 in Adelaide he married Charlotte's sister Ida; they had four sons and four daughters.